Neurology

In neuroimaging studies of anger, the most consistently activated region of the brain was the lateral orbitofrontal cortex. This region is associated with approach motivation and positive affective processes.

Physiology

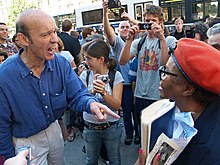

The external expression of anger can be found in facial expressions, body language, physiological responses, and at times in public acts of aggression. The facial expression and body language are as follows: The facial and skeletal musculature are strongly affected by anger. The face becomes flushed, and the brow muscles move inward and downward, fixing a hard stare on the target. The nostrils flare, and the jaw tends toward clenching. This is an innate pattern of facial expression that can be observed in toddlers. Tension in the skeletal musculature, including raising of the arms and adopting a squared-off stance, are preparatory actions for attack and defense. The muscle tension provides a sense of strength and self-assurance. An impulse to strike out accompanies this subjective feeling of potency.

Physiological responses to anger include an increase in the heart rate, preparing the person to move, and increase of the blood flow to the hands, preparing them to strike. Perspiration increases (particularly when the anger is intense). A common metaphor for the physiological aspect of anger is that of a hot fluid in a container. According to Novaco, "Autonomic arousal is primarily engaged through adrenomedullary and adrenocortical hormonal activity. The secretion by the adrenal medulla of the catecholamines, epinephrine, and norepinephrine, and by the adrenal cortex of glucocorticoids provides a sympathetic system effect that mobilizes the body for immediate action (e.g. the release of glucose, stored in the liver and muscles as glycogen). In anger, the catecholamine activation is more strongly norepinephrine than epinephrine (the reverse being the case for fear). The adrenocortical effects, which have longer duration than the adrenomedullary ones, are modiated by secretions of the pituitary gland, which also influences testosterone levels. The pituitary-adrenocortical and pituitary-gonadal systems are thought to affect readiness or potentiation for anger responding."

Neuroscience has shown that emotions are generated by multiple structures in the brain. The rapid, minimal, and evaluative processing of the emotional significance of the sensory data is done when the data passes through the amygdala in its travel from the sensory organs along certain neural pathways towards the limbic forebrain. Emotion caused by discrimination of stimulus features, thoughts, or memories however occurs when its information is relayed from the thalamus to the neocortex. Based on some statistical analysis, some scholars have suggested that the tendency for anger may be genetic. Distinguishing between genetic and environmental factors however requires further research and actual measurement of specific genes and environments.

Philosophical perspectives

Antiquity

Ancient Greek philosophers, describing and commenting on the uncontrolled anger, particularly toward slaves, in their society generally showed a hostile attitude towards anger. Galen and Seneca regarded anger as a kind of madness. They all rejected the spontaneous, uncontrolled fits of anger and agreed on both the possibility and value of controlling anger. There were however disagreements regarding the value of anger. For Seneca, anger was "worthless even for war." Seneca believed that the disciplined Roman army was regularly able to beat the Germans, who were known for their fury. He argued that "...in sporting contests, it is a mistake to become angry".

Aristotle on the other hand, ascribed some value to anger that has arisen from perceived injustice because it is useful for preventing injustice. Furthermore, the opposite of anger is a kind of insensibility, Aristotle stated. The difference in people's temperaments was generally viewed as a result of the different mix of qualities or humors people contained. Seneca held that "red-haired and red-faced people are hot-tempered because of excessive hot and dry humors." Ancient philosophers rarely refer to women's anger at all, according to Simon Kemp and K. T. Strongman perhaps because their works were not intended for women. Some of them that discuss it, such as Seneca, considered women to be more prone to anger than men.

Control methods

Seneca addresses the question of mastering anger in three parts: 1. how to avoid becoming angry in the first place 2. how to cease being angry and 3. how to deal with anger in others. Seneca suggests, in order to avoid becoming angry in the first place, that the many faults of anger should be repeatedly remembered. One should avoid being too busy or deal with anger-provoking people. Unnecessary hunger or thirst should be avoided and soothing music be listened to. To cease being angry, Seneca suggests "one to check speech and impulses and be aware of particular sources of personal irritation. In dealing with other people, one should not be too inquisitive: It is not always soothing to hear and see everything. When someone appears to slight you, you should be at first reluctant to believe this, and should wait to hear the full story. You should also put yourself in the place of the other person, trying to understand his motives and any extenuating factors, such as age or illness." Seneca further advises daily self-inquisition about one's bad habit. To deal with anger in others, Seneca suggests that the best reaction is to simply keep calm. A certain kind of deception, Seneca says, is necessary in dealing with angry people.

Galen repeats Seneca's points but adds a new one: finding a guide and teacher can help the person in controlling their passions. Galen also gives some hints for finding a good teacher.Both Seneca and Galen (and later philosophers) agree that the process of controlling anger should start in childhood on grounds of malleability. Seneca warns that this education should not blunt the spirit of the children nor should they be humiliated or treated severely. At the same time, they should not be pampered. Children, Seneca says, should learn not to beat their playmates and not to become angry with them. Seneca also advises that children's requests should not be granted when they are angry.

Medieval era

During the period of the Roman Empire and the Middle Ages, philosophers elaborated on the existing conception of anger, many of whom did not make major contributions to the concept. For example, many medieval philosophers such as Ibn Sina (Avicenna), Roger Bacon and Thomas Aquinas agreed with ancient philosophers that animals cannot become angry. On the other hand, al-Ghazali (also known as "Algazel" in Europe), who often disagreed with Aristotle and Ibn Sina (Avicenna) on many issues, argued that animals do possess anger as one of the three "powers" in their Qalb ("heart"), the other two being appetite and impulse. He also argued that animal will is "conditioned by anger and appetite" in contrast to human will which is "conditioned by the intellect." A common medieval belief was that those prone to anger had an excess of yellow bile or choler (hence the word "choleric"). This belief was related to Seneca's belief that "red-haired and red-faced people are hot-tempered because of excessive hot and dry humors."

Control methods

Maimonides considered being given to uncontrollable passions as a kind of illness. Like Galen, Maimonides suggested seeking out a philosopher for curing this illness just as one seeks out a physician for curing bodily illnesses. Roger Bacon elaborates Seneca's advices. Many medieval writers discuss at length the evils of anger and the virtues of temperance. John Mirk asks men to "consider how angels flee before them and fiends run toward him to burn him with hellfire."In The Canon of Medicine, Ibn Sina (Avicenna) modified the theory of temperaments and argued that anger heralded the transition of melancholia to mania, and explained that humidity inside the head can contribute to such mood disorders.

On the other hand, Ahmed ibn Sahl al-Balkhi classified anger (along with aggression) as a type of neurosis, while al-Ghazali (Algazel) argued that anger takes form in rage, indignation and revenge, and that "the powers of the soul become balanced if it keeps anger under control."

Modern times

The modern understanding of anger may not be greatly advanced over that of Aristotle. Immanuel Kant rejects vengeance as vicious because it goes beyond defense of one's dignity and at the same time rejects insensitivity to social injustice as a sign of lacking "manhood." Regarding the latter, David Hume argues that because "anger and hatred are passions inherent in our very frame and constitution, the lack of them is sometimes evidence of weakness and imbecility." Two main differences between the modern understanding and ancient understanding of anger can be detected, Kemp and Strongman state: one is that early philosophers were not concerned with possible harmful effects of the suppression of anger; the other is that, recently, studies of anger take the issue of gender differences into account. The latter does not seem to have been of much concern to earlier philosophers.

The American psychologist Albert Ellis has suggested that anger, rage, and fury partly have roots in the philosophical meanings and assumptions through which human beings interpret transgression. According to Ellis, these emotions are often associated and related to the leaning humans have to absolutistically depreciating and damning other peoples' humanity when their personal rules and domain are transgressed.

Hello Friends ! Please send your requests,comments,opinions or suggestions about this blog.

0 comments:

Post a Comment